Last time we discussed why diversification was important and how it can be measured. This piece will examine some common misconceptions about diversification as well as discuss some very practical limitations.

I often have a conversation that goes something like this; “I’m well diversified because I have a portfolio of several stock funds. My funds include small stocks, mid-sized stocks, large stocks, growth stocks and value stocks.”

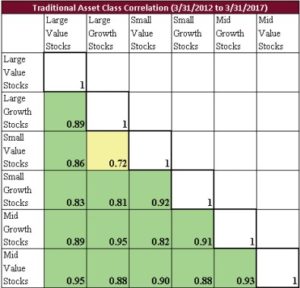

The table below shows the correlation between the various combinations of stock sizes as well as value and growth characteristics. It becomes immediately obvious that this “classic” methodology for diversifying one’s stock portfolio doesn’t really provide much systemic diversification at all! What the client is diversified from is the idiosyncratic risk of owning a single stock. In other words, an accounting scandal at SCAM, an incompetent CEO at OOPS or a massive customer food poisoning at YUK isn’t going to significantly impact his portfolio. I consider this false sense of diversification quite dangerous as the client has a significant disconnect between their perceived portfolio risk vs. their actual risk. The client should expect this type of stock fund portfolio to decline about the same as the general market averages, maybe even a little more since smaller stocks tend to be more volatile than large stocks!

There are better ways to diversify a stock portfolio than by simply using company size and growth/value attributes.

Another common mis understanding of diversification can occur in reviewing a client’s portfolio. As an example, a particular investment may have declined whereas their stock fund(s) are doing well. What is wrong with the laggard? Well, perhaps nothing, it may be an investment that does best when stocks are under stress. If stocks are behaving very well then it shouldn’t be a surprise that this element isn’t. Selling that poor performing investment while stocks are climbing may be regretted later when stocks actually decline. If we reduce or sell that position simply because it has declined we may be undoing the diversification element that was purposefully included in the portfolio when it was constructed. There are certainly times when an investment should be sold after a price decline but the price decline itself is not a robust reason to sell. A deeper understanding is required to make an intelligent decision. A better question to ask would be, “given the present market environment, is this element of the portfolio acting the way we expect it to”?

Diversification is sometimes referred to as the “only free lunch” in investing. This is because Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) teaches us that effective diversification can reduce risk and increase returns!

OK so we’ve strongly suggested that diversification is a very good thing to design into a portfolio. And it is but it isn’t a silver bullet. Why?

Diversification will not prevent a loss in a down market.

In most portfolios stocks are a significant portion of the total assets. Stocks are generally the most volatile assets, their prices fluctuate more than other asset classes, and thus the majority of the portfolio risk is associated with stocks. Therefore, if stocks are in a general decline one must expect their overall portfolio value will also decline. What effective diversification can do is to reduce the magnitude of the decline. This can be tremendously beneficial. An even better scenario would be to allocated some capital to stocks whose historical returns are not strongly correlated to the general market.

Correlation Coefficients are not static.

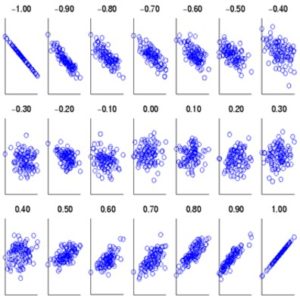

Whenever a correlation coefficient is calculated a given set of data points are analyzed. Therefore, the specific R value is dependent on the precise timeframe analyzed. This is generally not a problem. The R for a large cap value fund may vary between 0.8 and 0.98 relative to the S&P500 but whatever the exact number turns out to be doesn’t change the fact the two are highly correlated.

In a financial crisis, all risky assets tend to decline

This is the much more troublesome reality. In a market sell-off nearly all risky assets decline simultaneously. In other words, just when you need it most the correlation between many risky assets tend to increase thus reducing the benefit of diversification. Why? In a true panic or market crisis participants change their behavior abruptly and in mass tend to sell risky assets and move their money to safety. Think lemmings and cliffs! The takeaway is that effective diversification can be a powerful tool to increase returns and decrease risk but in a declining market diversification alone cannot be expected to prevent a portfolio’s value from declining. However, assuming your portfolio is well aligned to your risk tolerance and risk capacity hopefully you aren’t following the herd over the cliff. Instead, for the patient value investor this may represent an excellent opportunity to buy high quality assets when they go on sale!